Representatives from federal civil law enforcement agencies implored US Senators on Wednesday to ditch legislation that would require them to obtain warrants before reading Americans’ emails.

The pleading came during a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing focused on the ECPA Amendments Act—proposed legislation that would update the 1986 Electronic Communications Privacy Act (ECPA) by creating privacy protections for emails, texts, and other information stored in the cloud.

“The Department remains concerned…about the effect a blanket warrant requirement would have on its civil operations.” Elana Tyrangiel, an official within with DOJ’s Office of Legal Policy, told lawmakers.

She claimed that “civil investigators enforcing civil rights, environmental, antitrust, and a host of other laws would be left unable to obtain stored communications content from providers” if they first needed a federal judge’s permission.

Her concerns were echoed by witnesses testifying on behalf of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC).

Civil enforcement agencies have taken advantage of what critics say is an outdated law to compel, with only a subpoena, the release of private emails stored for more than 180 days on third party servers.

The ECPA Amendments Act seeks to raise the bar before third party data reproduction to a probable cause warrant.

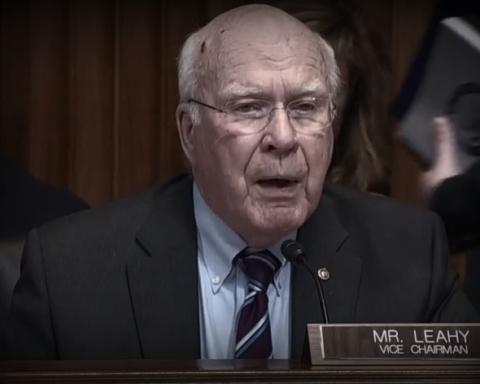

“We want these agencies to be effective, but they must abide by the same constitutional constraints that apply to everyone else,” said Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt), the committee’s ranking member and a co-sponsor of the ECPA Amendments Act.

“We do not expect our private letters or photos stored at home to lose Fourth Amendment protection simply because they are more than six months old. Neither should our emails, texts, or other documents we store in the cloud,” he added, during his opening remarks.

Sen. Leahy went on to criticize the SEC’s Division of Enforcement Director, Andrew Ceresney over the broad powers the agency was asking for in skirting warrant requirements.

“Are you seeking wiretap authority?” Leahy asked. “You do want to be able to read emails without a warrant.”

“What about listening to your targets phone calls?” the Senator followed up. “Wouldn’t that be more efficient—more effective?”

Another co-sponsor of the legislation, Sen. Mike Lee (R-Utah), chastised the panel of witnesses, when they all hedged in response to his question about whether the government should be able to read individuals’ emails without a warrant.

“I think the overwhelming majority of the American people would be very disturbed to hear that that question can’t be answered with a simple ‘no,’ that the government should not be able to get at peoples emails—the content of their email—without a warrant,” he said.

Sen. Lee raised the possibility that information gleaned from servers without a warrant through a civil investigation could be shared with criminal investigators, even though the latter require probable cause.

“You can understand how that could easily be manipulated in order to avoid the warrant requirement,” he noted.

There was one Senator, however, who sympathized with the witness panel’s concerns.

“What sounds like some good theoretical idea can have a major and detrimental impact on the ability of the people of the United States to have order—to avoid multiple frauds and thefts and computer abuses and violations of their privacies and things of that kind,” Sen. Jeff Session (R-Ala.) told the committee, before relaying a personal story about magazine subscriptions and corporate surveillance.

“I ordered a publication not long ago, and within a few weeks I get—I don’t know how many more selling me different kinds of a publications of a similar nature so somebody is sharing information all over,” Sessions said, adding that “all these things are available to the private sector and political candidates, and we have to be sure that we’re not placing too much of a burden on law enforcement.”

Sen. Leahy mentioned earlier in the hearing, however, that the FBI is already obtaining a warrant requirement during criminal investigations when seeking electronic communications regardless of age.

“This bill that Sen. Lee and I have would not change FBI procedure in that regard,” he stated.

Leahy also pointed to a 2010 US Court of Appeals ruling in United States v. Warshak that granted fourth amendment privacy protections to emails stored on third party servers, which has since subsequently barred agencies from obtaining emails without a warrant.

“Our bill would not alter that status quo,” Leahy said.

The ECPA Amendments Act has 23 cosponsors in the Senate. A companion bill in the House has over 292 supporters.