A Department of Justice Inspector General report suggests that top agents in the FBI may have suppressed information about Bureau capabilities in order to get a court order that could have drastically undermined consumer data security.

The watchdog’s findings show that after the December 2015 San Bernardino shootings, Bureau agents were zeroing in on a method to break into one of the shooter’s iPhones, while at the same time FBI leaders were telling Congress and the courts that no such capability existed.

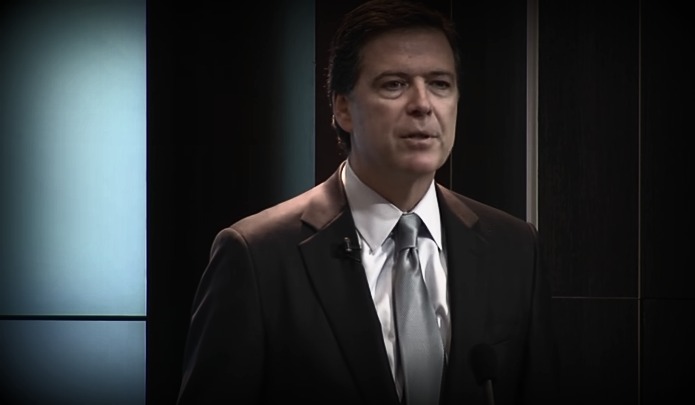

Ultimately, the IG concluded that former FBI Director James Comey didn’t lie to lawmakers when he claimed on February 9, 2016 that the bureau couldn’t hack into Syed Farook’s phone. Nor did the FBI lie in court filings a week later, when it took action against Apple to compel the company to break into its encrypted device.

The report instead pointed to a lack of communication between FBI assets to ensure there were no in-house or contractor solutions available before going to court.

For example, the IG learned that one day before the FBI filing against Apple, the chief of one of the Bureau’s hacking divisions—the Remote Operations Unit—had “only just begun the process of contacting vendors about a possible technical solution for the Farook iPhone.”

The report went on to note that the unit chief knew at the time of the filing that one of the vendors was “was almost 90 percent finished with a technical solution that would permit the exploitation of the Farook iPhone.”

Consulting the Remote Operations Unit was a “step that should have been taken,” according to the IG, “before making any conclusions about…capabilities or the larger question about whether compelling Apple to provide technical assistance was truly necessary.”

A month after its initial filing, the FBI informed the court that it had found a way into the alleged shooter’s phone, and no longer required Apple’s assistance.

A court order forcing Apple to unlock an encrypted iPhone would have set a new legal precedent that would have fundamentally weakened cryptographic technology, which has proliferated across the consumer market to thwart data thieves.

The FBI has routinely referred to the spread of encryption as a “Going Dark” problem, a term popularized by Comey himself, in his many appearances before Congressional committees.

According to testimony provided to the inspector general by former FBI Executive Assistant Director Amy Hess, this characterization of encryption led some Bureau officials to explicitly use Farook’s phone to seek out a controversial, privacy weakening court order.

“She became concerned that the [FBI’s] Cryptographic and Electronic Analysis Unit [CEAU] Chief did not seem to want to find a technical solution, and that perhaps he knew of a solution but remained silent in order to pursue his own agenda of obtaining a favorable court ruling against Apple,” the report stated.

Speaking to IG investigators, Hess described the Farook iPhone case as the “poster child” for Going Dark.

The CEAU chief later admitted to the watchdog that “after the outside vendor came forward, he became frustrated that the case against Apple could no longer go forward.” His identity was not disclosed in the report.

The FBI responded to the IG’s findings by stating that it is “taking further steps to address the circumstances that contributed to this incident.”