The highest court in the US on Monday announced it would take up a case that pits the well-being of an endangered amphibian against the interests of private developers.

Louisiana landowners are asking the Supreme Court to overturn a decision by the US Fish and Wildlife Service that classified 1,500 acres of land as a critical habitat for the dusky gopher frog.

The designated tract cuts right through property owned by timber company Weyerhaeuser, which had intended to use the land for residential and commercial development projects.

There are roughly 100 dusky gopher frogs left in the wild.

The species does not currently reside within the areas designated by the US Fish and Wildlife Service—a major point of contention by the private landowners. The agency, however, has determined that ponds and other habitats on the land are historic breeding grounds for the frog, and in need of protection for the species’ long-term health.

Plaintiffs are claiming that as a result of the government’s protections for the endangered frog, which were implemented in 2014, landowners lost out on $34 million.

Weyerhaeuser, however, has already lost twice in the courts. The Fifth Circuit affirmed last year the US Fish and Wildlife Service’s right to designate private land as critical habitat for an endangered species (even if the species doesn’t currently reside on the land). A full federal appeals court later denied the company’s bid for rehearing.

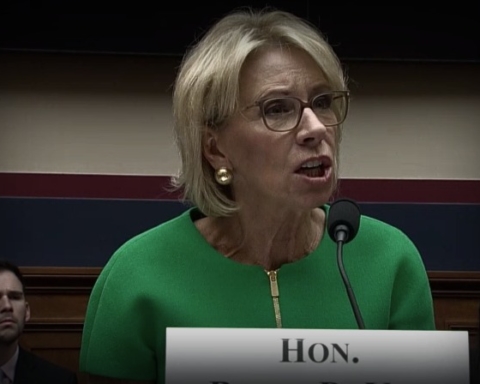

The Supreme Court could be more sympathetic to the concerns of the private developer, according to environmental groups.

“The Supreme Court’s ruling is bad news for these endangered frogs,” said Cynthia Sarthou, the executive director of the Gulf Restoration Network. She added that the suit intends to “gut essential habitat protections for the frog.”

Energy Law Blog reports that the case could hinge on a 1984 case involving Chevron in which the court held that it should defer to agencies to interpret ambiguous language in federal law.

The newest member of the court, Judge Neil Gorsuch has previously stated that the court’s conclusion in that case was a “judge-made doctrine for the abdication of the judicial duty.”